It’s Real Squid Game Hours

Let's just get this out of the way: You know Squid Game. You've heard of Squid Game, you've seen the memes, you've probably seen the show, and if you haven't, you stop reading this right now. You know it's written and directed by Hwang Donghyuk, features beloved A-lister Gong Yoo for maybe a cumulative six minutes, and it's quickly growing to be the most-watched Netflix original ever made. Squid Game is hot, and it's worth the hype. Even with my set of qualms, overall it's a positive experience—unless you don't like blood, peril, or general distress.

Fair warning: There will be spoilers. And maybe some blood.

To recap, Squid Game is about a system of soliciting and extracting desperate people—in this case, a gambling addict who can't support his daughter, a Pakistani migrant worker who's been working months without pay, a North Korean defector, and a former gifted SNU student-turned-embezzler—to participate in children's games with the promise of death or a hefty cash prize. The participants, whose lives have been assigned an individual value of ₩100,000,000 (~$83,500 USD), run a six-day gauntlet for the entertainment of spectators who all have three things in common: they're rich, they're white, and they're men.

It's important to note that the viewer only becomes aware of the spectatorship due to a B-plot where a detective infiltrates the game location to find his missing brother, but also to show us what's going on behind the curtain; which includes the bets being placed on players' lives and the organs being harvested from the piles of bodies left behind. The participants of the games know they're being watched, but never by whom, and it forces them into a position where they can only blame each other for the hardships they experience.

The social commentary in Squid Game is laid out pretty clearly, though I acknowledge that there's only so much I can absorb as a non-Korean, American viewer. There's realism in the statement that a capitalist system only serves to hurt its people, save for the handful at the top who are in a position to needlessly exploit marginalized people for personal gain and largely without consequence—after all, they're behind the curtain.

The marginalized people depicted here (the Korean underclass, women, elders, a dark-skinned foreigner who risks alienating himself further if he doesn't constantly overdo his politeness, etc.) enter on the same terms—they need money, they want money, they don't have money, or all of the above. Villains are made among them in #101 Jang Deoksu (Heo Sungtae) as he antagonizes every other player for seemingly no functional reason, but also in #218 Cho Sangwoo (Park Haesoo), Gihun’s childhood friend who quickly shows self-prioritizing behavior; which, juxtaposed with main character Gihun's (Lee Jungjae) selflessness, makes him out to be a sneaky bad man. But Deoksu and Sangwoo are just as trapped as everyone else. Sure, I don't agree with their methods and often they're just mean, but they're not really the enemy.

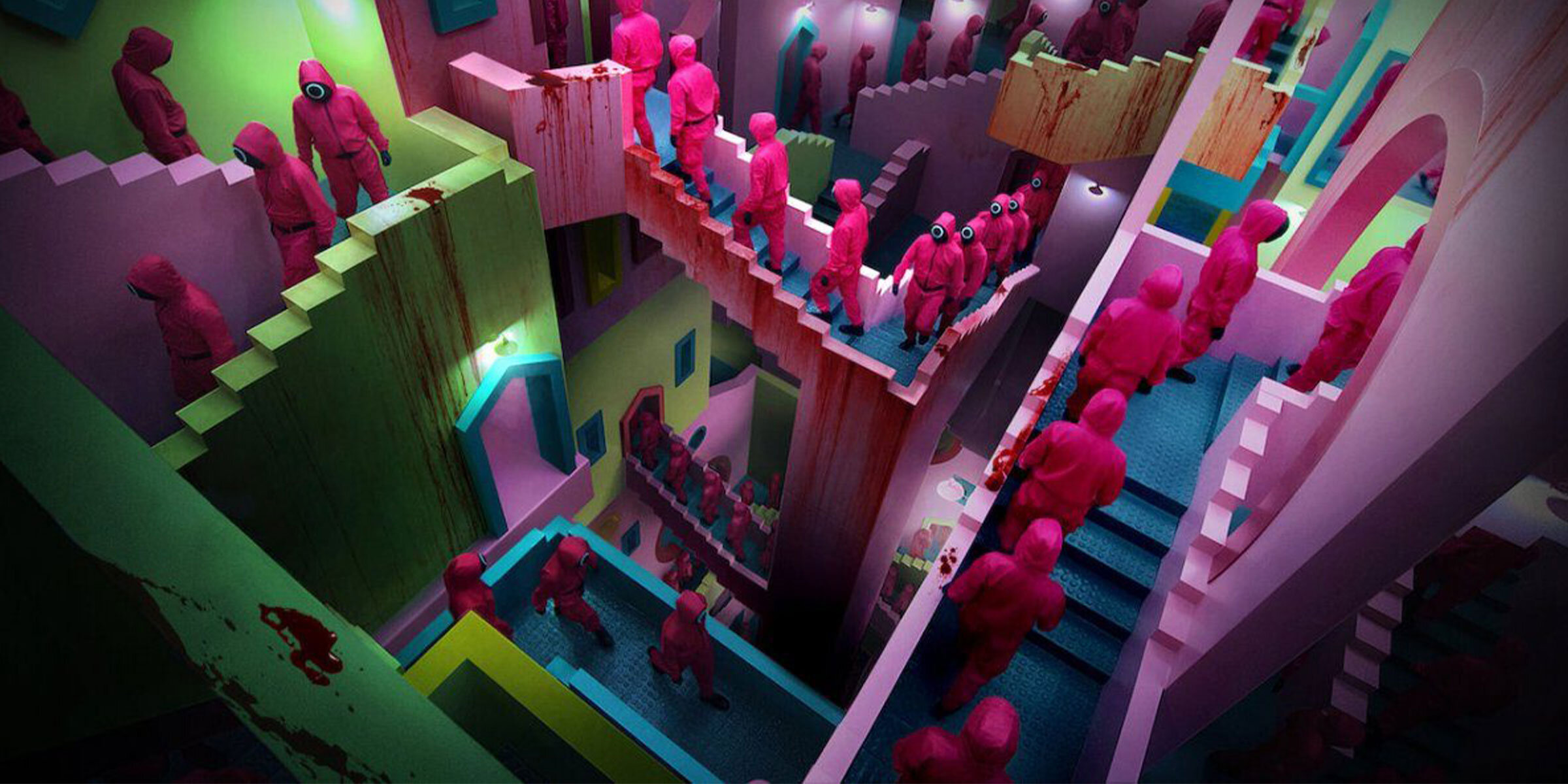

Bodies pile high in just the first game, after which only 201 of the 456 participants remain—and with respect to the obvious differences between real and fictional violence, there's some irony in the framing of the spectators of the Squid Game as fundamentally corrupt sickos when Squid Game is about to be the most-watched show in Netflix history. By the end, there is indeed only one winner, and we learn that #001 Oh Ilnam (Oh Yeongsu), an elderly man who was gung-ho to play but who apparently has a relatively nihilistic outlook on life, didn't die when we thought. He confesses that he joined the game at will, with desire to remember the feeling of playing with friends as a child (after all, it's more fun to play a game than to watch it), but also as a social experiment to determine just how inherently good humanity is. Here we're filled in on the intent of the game's existence, which is entertainment, but it also feels a little bit like The Purge, as a “justifiable” large-scale massacre of people who've been deemed expendable by people, like Ilnam.

Ilnam dies before he and Gihun finish a final game of "Will Somebody Help The Dying Man On The Street?," fully cemented in his belief that people are selfish, ruthless creatures incapable of doing good without expectation of personal gain—despite playing four games with Gihun, who encouraged teamwork and good spirits from the beginning and protected those close to him until the end, even when he knew they might not do the same for him.

If there’s one thing that really makes Squid Game notable, it’s that it takes the “people play games and hope they survive” story that is often told alongside “capitalism is bad” as an overall message, but it doesn’t place it in a sci-fi/fantasy setting that separates the viewer from some unknowable fictional reality. While some characters are a little formulaic in behavior (re: tropey), others feel real because they are real, and that’s where the connections are made.

Squid Game is good stuff, but it falls off a bit at the halfway point, which is a shame. When half the main cast is killed off in episode six, the whole affair slows exponentially until the very end, and it’s in part because some of the details feel a little aimless. The show ends on the note of Gihun not having touched his winnings, about to board a plane to visit his daughter who’d just moved to America. On his way there, he sees someone else about to fall into the same Squid Game trap he had, playing ddakji with the mysterious Salesman (Gong Yoo). Gihun reaches them as the Salesman is leaving, but in time to stop this new recruit from contacting him, stealing his card so he can call them himself—only to find out another Squid Game is about to start, so he forgoes his plane ride, presumably to stop it.

At this time, there is no promise of a second season, which isn’t a surprise given Squid Game hasn’t even been out for a full month yet. While I’m not sure it really needs one, a second season could make sense of the bits that feel like loose ends.