Fandom: Power to Move the World

Social Phenomena: We Before I

In Korea, there is greater importance to act as a group or community rather than individual selves. There is a strong sense of togetherness, putting the team before considering what you need or want for yourself. Most apparent in work spaces, schools, and even in families, this social phenomenon has long been an underlying sentiment in Korea’s social culture, but beyond that, being part of a community or a group gives people a sense of belonging.

This can explain the psychological phenomenon of the “bandwagon effect” that is common in Korean society. An example of this is fandom (a compound word of “fanatic” and “kingdom”) culture, most vividly seen among K-Pop artists. Even if it is not the case today, the earlier fan culture may have been merely a trendy epidemic, but fandom culture has been evolving into more than simply two entities in a relationship. Fans and celebrities have an unbreakable bond which allows them, together, to potentially form empowering influence and shift the world.

Early Groupies: Start of Fan Culture

Image: Naver Blog, jisg7

The beginning of fandom, a new social hype, began with one of Korea’s most influential singers, Cho Yongpil’s Oppa Bu-dae (오빠부대)—a group of fangirls. It was a “new type of fan(dom) culture” of unfiltered explosions of emotions. Oppa Bu-dae—literally translated as “Oppa (older brothers or older male figures to younger females) Corps”—was formed in the 1980s after Cho released his first album Woman Outside The Window.

With the timely introduction of television, fans’ activities and raw ways of supporting and cheering for their stars were wholly exposed. There were fans formed around singers that preceded him such as Nam Jin and Na Hoona in the 1970s, but not much of the fan behaviors or activities were known, other than that they deliberately filled up the very front row of each concert of the artist that they were supporting. Cho Yongpil’s fans still remain, to this day, known as The Great Birth (위대한 탄생), Club Mizi (미지의 세계), and Eternally (이터널리); most of those who were in their teens and were told to go home by Cho during his prime years now support Cho by sharing life's wisdom or wise advice like, “Oppa, the world is not so naive. Please live calculatively.”

In these early years, fans’ expressions of love and support for their celebrities were more aggressive than today. Their actions were often impulsive, disruptive, and radical. Breaking the stage and shattering glass windows of the buildings from banging on them were ordinary happenings. Following celebrities around wherever they went, to their concerts, events, broadcasting schedules, homes, hangouts, personal meetings, and intruding on their privacy started to be taken as a celebrity's burden, something that comes with the job of being a star. The ‘80s fans were true to their hearts—their feelings were so unconditional and blind. One notable incident was when Cho held his 35th anniversary concert and over 50,000 fans wearing poncho raincoats came to stay beside (or in front of) him for two hours in pouring rain. At that time, Cho’s Oppa Bu-dae were sensational and redefined the relationship between the celebrity and the fans in Korean popular culture.

1990s: Fan Culture of First Generation Idols

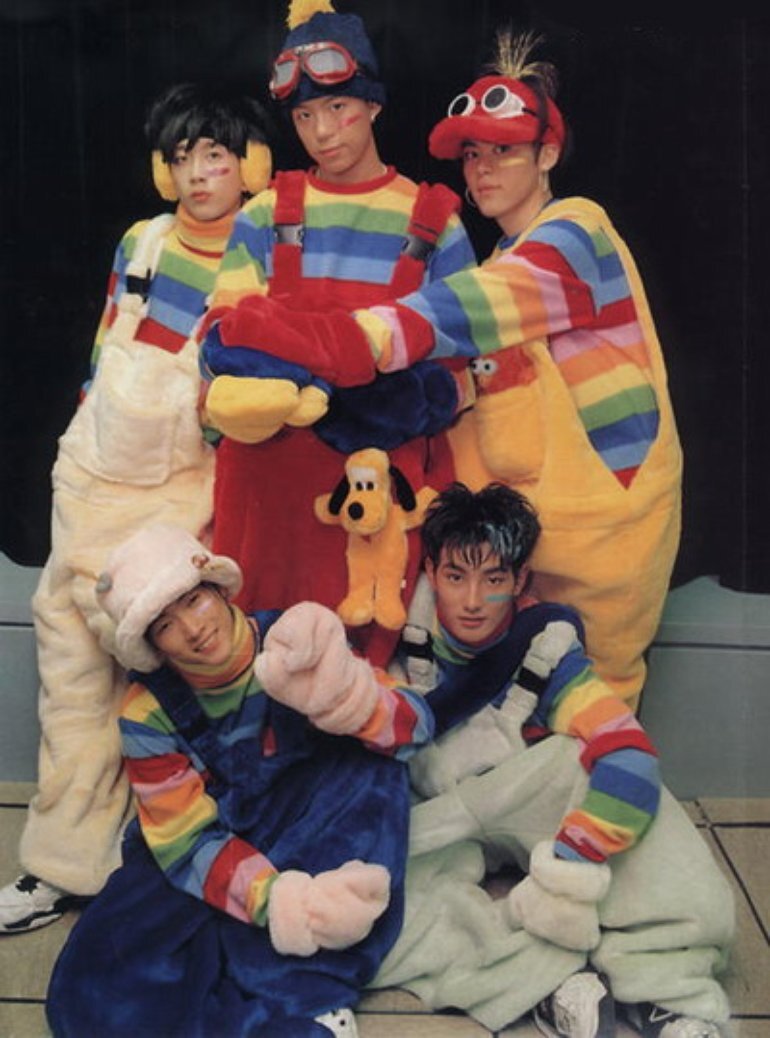

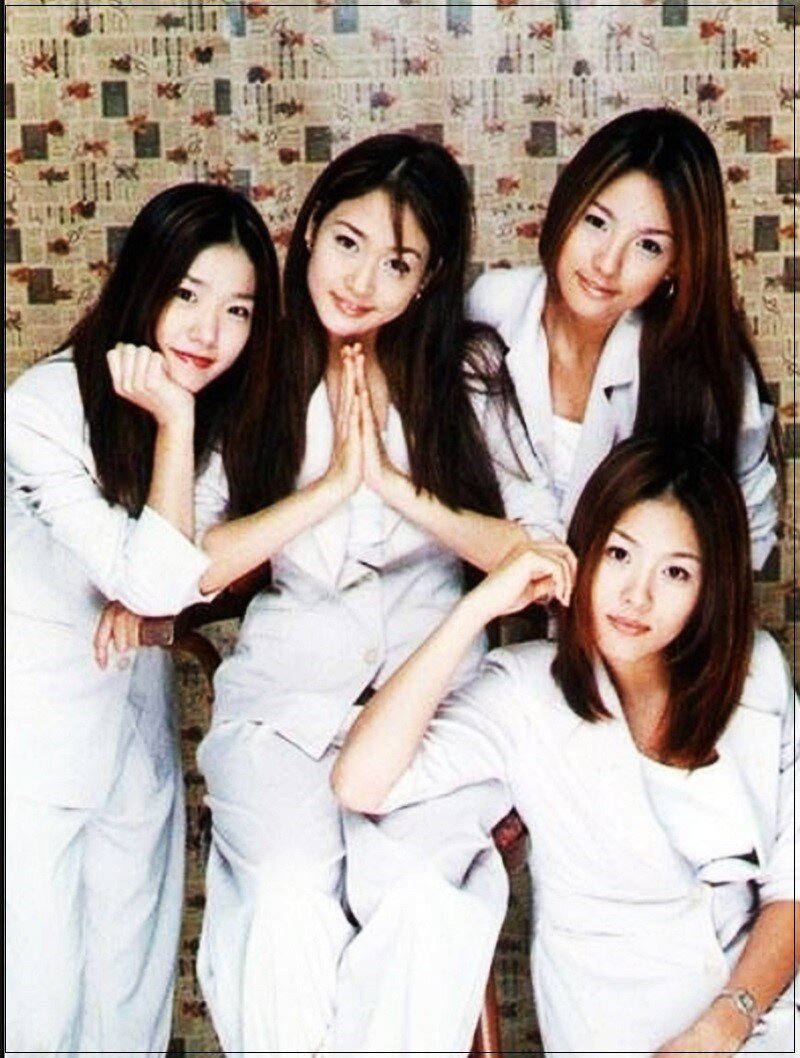

Image: last.fm Image: Naver Blog 공간건설

In the 1990s, what used to be a mere “fanatic” group of individuals who were all dispersed and alone in supporting stars, developed into a systematic community, or a “kingdom,” of their own, where they revered their celebrities. Most of these fandoms centered around first-generation K-Pop “idols” (these pop stars were produced by the labels to be like idols to the young generation) and the “number of voluntary fanclubs increased progressively.”

The fan activities and participation were still impulsive and dramatic, but these fan communities each had an organized system and management which officially came to be called “fanclubs.” The substance of the fanclubs was in the form of an online community platform led by a voted president in a strictly hierarchical pyramid. A flock of 20 to 30 fans went and acted desperately around celebrities such as g.o.d, H.O.T, Fin.K.L, S.E.S, SECHSKIES, SHINHWA, or Seo Taiji and Boys to get a glimpse of them, be noticed by them, or just to simply get closer to them. But only the members at the top level had chances to communicate directly with their celebrity, while the rest of the members called a number to receive one-way announcements about their celebrity through voicemail from the club president. Messages sounded a lot like: “On the ninth, oppas have plans at 7pm at the Seoul plaza so come gather at the entrance.” They truly did their best to make full use of the technology available to them for their time.

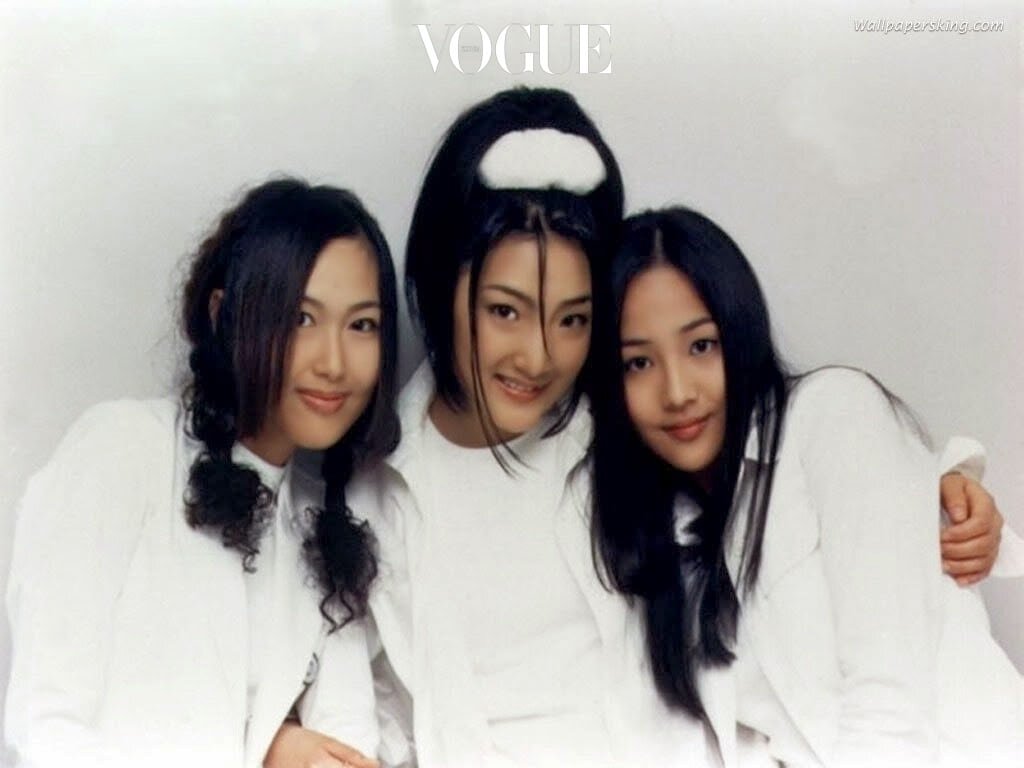

Image:Vogue Korea

Image: Hyunghyang shinmun

Fans’ pure and down-to-earth love for their celebrities was reflected through fan-made goods and products. They cut out photos from magazines and papers to decorate their box pencil cases, pencil boards, bookmarks, and more. They imitated hairstyles or fashion styles of the star they admired. Fanclubs often presented their idols with small gestures such as foods, clothes, or accessories, but the value of these presents grew larger. Eventually fans began collecting money to give celebrities luxury brand items such as bags, jewelry, clothes, and even cars.

Their attitudes towards anti-fans or someone involved in a scandal with the artist that they supported were ruthless. Some anti-fans received mail with sharp blades inserted at the corner of the envelope so they would hurt themselves when opening it, and a person involved in a romantic scandal with their idol received images of their body parts from magazines cut out in pieces. Celebrities received blood-written letters and had their houses often trespassed by a few fans who went overboard and disrespected their privacy—these bad-mannered fans are called sasaeng fans.

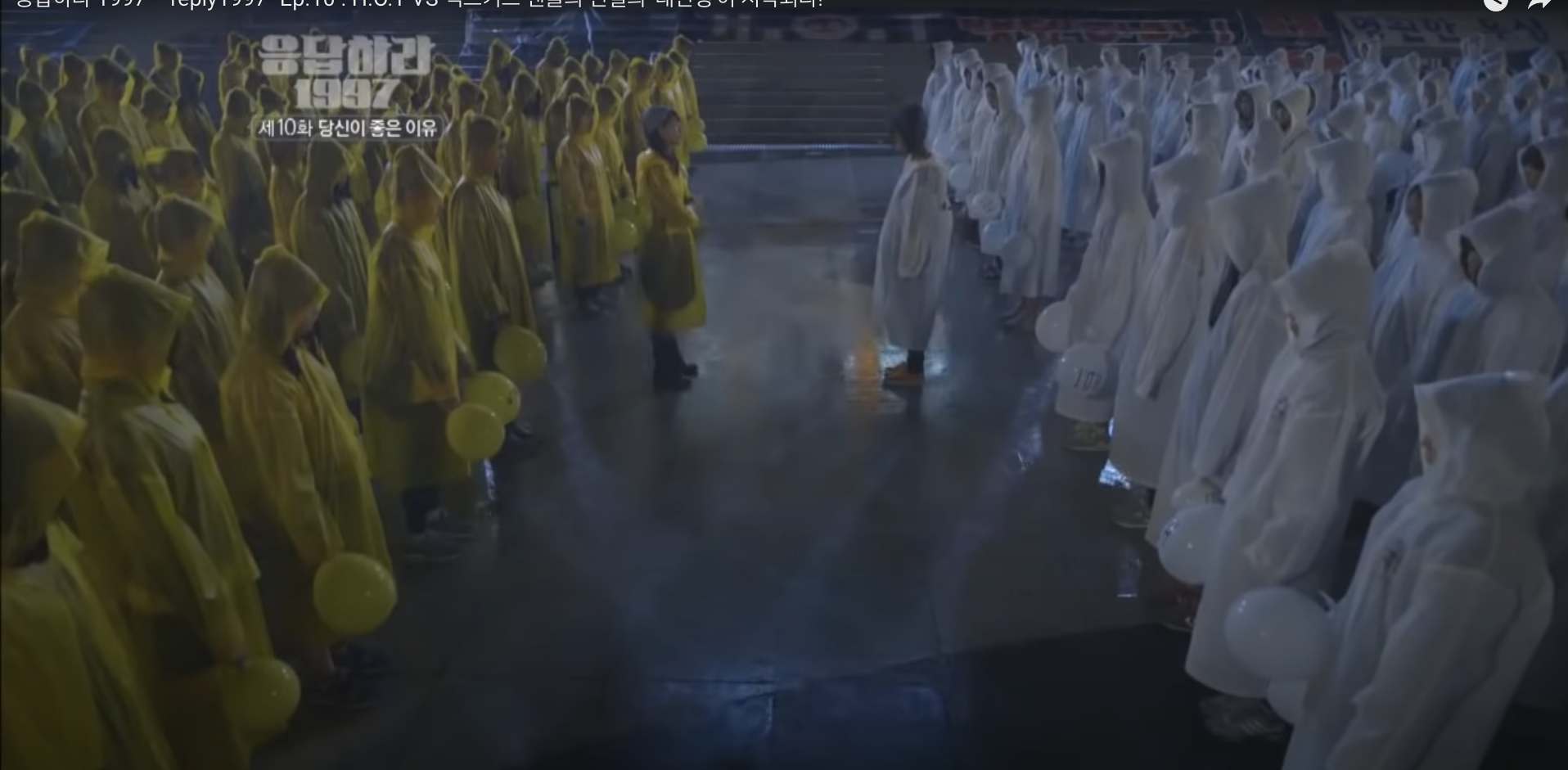

Image: CJ ENM ‘Reply 1997’

A scene in the Korean drama Reply 1997 elaborately portrays this hype and social craze for the K-Pop idols in this era. The scene draws on the heated rivalry between SECHSKIES fans and H.O.T fans over who would win the grand prize. The fans glared at each other in pouring rain wearing their designated colored raincoats, with SECHSKIES fans holding yellow balloons and H.O.T fans holding white. 250 fans gathered in front of the National Theater of Korea, where an award ceremony took place. Conflicting over who would be the winner of the award, they mercilessly attacked each other. This scene is said to be based on a real event in 1997 known as the “1997 Legendary Gang Fight.”

1990s fan culture was a significant transition from the 1970s and 1980s because this changed the values and roles of the fans in popular culture. It was a time where many who were involved in the industry contemplated the influence that celebrities may have on people and the relationship between them. Thus, fan activities were no longer just a chaotic craze or obsession, but a way for the fans to live a lifestyle. It was a chance to live their ideal that they only dreamed of. Fandoms became more official and had organized ways of running them. Fans were way beyond honest and organic about their own feelings. They revered and worshiped their celebrity, but the efforts to interact and connect with celebrities were yet to mature.

2000s: Matured Love

In the 2000s, fans started to act more as a protector or spokesperson of celebrities. Unlike previously, when they were only eager to deliver their undivided attention and love, they started to sincerely care for each other and their stars, taking into consideration how their words or behaviors would affect their celebrity. The system of fanclubs was designed for the success of the celebrity. With the development of social networks and media, fans' diligent efforts spread over the national boundaries and reached people around the world to create international fans. They found smarter ways to show their support and love. The power and strength of their activities became clearer and more conspicuous.

The operation of fanclubs in the 21st century has become much more commercial. In place of the club president is what is called a “fan manager,” who is usually from the label company of the celebrity. Goods and products that fans made for themselves in the 1990s are now merchandised products. Imitating the celebrity’s style was no longer the trend, instead it was important to be who you are and to love yourself. What used to be a one-way communication has become more casual and regular, hanging out through social media postings or live channels. Fan activities are also very focused on considering how a certain act would reflect on the image of their celebrity.

Recently, in celebration of iKON’s six year anniversary since their debut, the group and their fan community (iKONICs) WITHiKON made a donation of 2,730,000 KRW in iKON’s name to help provide “musical education for the disabled children and low income underprivileged teens.”

One of the most nationally polemic incidents appeared when CBS Sunday Morning interviewed BTS with host Seth Doane in 2019. After the interview was aired, the Korean ARMY was deeply disappointed to see CBS carelessly use a map labeling the East Sea as the Sea of Japan. BTS fans, both local and international, complained and demanded the label on the map be revised. Anyone who knows the background of Korea’s ongoing diplomatic and political sensitivity with Japan would know this has been in dispute for years. Historically, Japan used the name to their own advantage, to show off their imperialistic authority and power during the time of colonization of Korea. Before that point, the ocean was officially called the East Sea, which is the correct term. Korea has long been trying to spread the correct awareness to the world. Afterwards, CBS uploaded a new version of the interview where the label “Sea of Japan” is deleted. To the Korean people, “this phenomenon of the Sea of Japan label having been deleted is deeply meaningful” and historic.

In 2020, CNN reported interesting news that K-Pop fans protected the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement during the protests after the death of George Floyd. Fans uploaded countless memes and fancams of their favorite K-Pop artists, such as EXO, BLACKPINK, and BTS, with the hashtag “#WhiteLivesMatter” to drown out anti-black postings that would barricade the BLM movement. Now when they search “#WhiteLivesMatter” or “#WhiteOutWednesday,” people see K-Pop artists’ reels and photos that are completely unrelated to stopping the BLM movement. CBS introduced K-Pop fandom as “one of the strongest forces on social media” with “tens of thousands of K-Pop fan accounts posting over six billion tweets last year.” Unlike the past, fans have matured and are contributing to do good both internationally and locally. Now, fandom has really positioned itself as a culture that is uniquely shared globally.

Closing Note: From Idolization to Life Partners

Today, fans participate in various ways to love and support their celebrity in a more mature way. They are involved in a psychological “symbiotic relationship” in that through their stars, the fans live the ideal that they long for and the celebrities achieve self-actualization or desires to be accepted (or compensated for their hard work). They are “mentally, psychologically, and emotionally immersed in one another,” nearly becoming one. Over time, people’s level of social awareness has greatly matured. The fans’ actions started to base themselves on respect and care for not only the celebrity, but also each other. In return, celebrities share and interact with fans in every way possible, through lyrics of their music, various social media contents, concerts, handwritten letters, variety shows, talk shows, and more. This kind of attachment between star and fans is all the more personal and precious, evolving from unilateral worship to a healthier bond as life partners, truly manifesting their potential to change the world.